How will technology really help us meet our national health objectives?

Hospital + Healthcare speaks to RMIT Technology Professor Kate Fox about which up-and-coming health technologies are likely to become realities, and which are simply hype.

As a young girl, Technology Professor Kate Fox of RMIT had a technophilic fascination with the hit TV series CSI Miami.

“I was amazed by the way detectives could trace criminals from a single fingerprint, and other such sorcery,” she recalled.

Later embarking on a career in technology research, Fox quickly grew disheartened. Fingerprints could of course be used in criminal identification, but the method was far from infallible, with experts often getting the matches wrong.

This gap between science fiction and reality is also evident in health care — a sector in which Professor Fox now specialises. She believes premature media reporting may be partly to blame.

“News coverage tends to generate a lot of excitement about emerging tech, when in reality, many of the products we hear about are just in their early experimental phases — some of them never making their way into clinical practice,” she said.

As such, many people — including clinicians — may be disillusioned about the short-term potential of health tech.

“In a previous role, for example, I worked on a pioneering bionic eye project. We made implants for treating blindness and retinal disorders. It was great, but there was this expectation that we could cure blindness and restore the world’s vision — when really it was just three patients that had to stay attached to a computer the whole time the technology was in use.

“All this tech looks great in a 10-minute news feature, but we need to manage people’s expectations,” she added.

Sorting fact from (science) fiction

So which tools can clinicians really expect to enter mainstream practice in the coming years, and — of those — which ones will make a valuable difference?

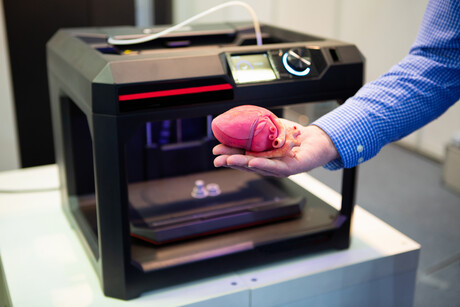

“In a word: bio-printing,” Fox said. “It’s pretty much the ‘Holy Grail’ of health-tech innovation — printing a person’s tissues and cells to make major organs. Some of the tech is a long way away, but the rest is closer than you think.”

Among those on the near horizon is a 3D-printed heart, after researchers in Israel recently manufactured a miniature prototype.

“It’s the size of a thumbnail and, as such, would never be suitable for human use in its current state. For that to happen, researchers need to prove the organ can survive at scale and maintain blood flow — not just on a lab bench, but inside a person. Nonetheless, it shows us that cardiac tissue can be printed — and that’s an amazing feat.

“As researchers continue experimenting with these prototypes, we’ll no doubt see higher-resolution images and better outcomes in the months and years to come. We’re already getting very close with dumb organs, like the skin, liver and kidneys,” she added.

Augmented- and virtual-reality are other areas showing genuine promise, on the short-term horizon.

“Surgeons can now go and practise surgery in a virtual environment, where they can understand a person’s vasculature, practice cuts and play with tools — without the risk of patient harm. This is actually happening in the world now,” Fox said.

Companies like Adelaide-based Fusetec are also helping on this front — manufacturing fake tissue for surgical training.

“The 3D materials they have made look and feel like human tissue and can be coupled with augmented reality to practise surgeries. Combine these two technologies, and surgical simulations are even closer to the real deal. It’s definitely a tech to watch out for,” Fox said.

Finally, 3D printing is set to change the way researchers look at implant engineering.

“Historically, if someone needed a hip or a knee replacement, they would go to an implant shop and buy one off the shelf. With 3D printing, you can get an implant designed specifically for your body and custom fit it to whatever condition you are trying to treat.

“For example, in the treatment of osteosarcomas — where patients often get a whole heap of bone removed — you can replace that bone and reduce the amount of margin taken up by an implant. It’s is a pretty nice outcome,” Fox said.

Avoiding the techno-hype

With hundreds of news reports coming out each day — promising the ‘next-best healthcare innovation’ — how can clinical leaders avoid getting swept up in the techno-hype?

“As clinicians we need to manage the expectations around what is real, valuable and available. Keep in mind that tech companies want to get out there and promote their piece as early as possible — even if they are a long way away from getting all the necessary approvals.

“My advice is to take news coverage with a grain of salt. What might be painted as the ‘new frontier’ could just be another CSI problem — yes, there is a technology that identifies people from their fingerprints, but it is rarely as simple as it sounds,” she concluded.

From vision to vigilance: building a secure digital future for health care

Digital health adoption offers clear benefits, yet Australians continue to scrutinise how their...

In Conversation with Australasian Institute of Digital Health CEO Anja Nikolic

Hospital + Healthcare speaks with Australasian Institute of Digital Health CEO Anja...

Cutting-edge digital health tools putting plastic, silicon and steel to the sword

The Australian Digital Health Agency's Chief Digital Officer sets out some sustainable...

![[New Zealand] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89856/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)

![[Australia] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89855/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)