Hospital violence: we can reduce it

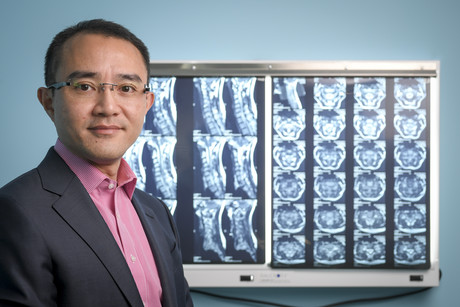

In 2014, surgeon Dr Michael Wong survived a vicious knife attack in the foyer of the hospital where he worked. He wants his story to raise awareness of security weaknesses in hospitals.

It was a regular day at work; nothing special, nothing out of the ordinary, the morning that Dr Michael Wong hurried through the sliding doors and into the foyer of the Western Hospital in Footscray, Victoria. A neurosurgeon, spinal surgeon and a full-time staff member of the public hospital, he was juggling an enormous workload and was ready to start his day.

Surrounded by people in the busy foyer, it didn’t occur to Dr Wong to feel anything but safe — until he was accosted by a patient. Pulling a small knife from his pocket, the man began to stab him repeatedly.

Shocked bystanders sprang into action. Hurling a bag and a small sign at his accoster, they distracted him momentarily, allowing them to pull Dr Wong through the double doors of the emergency ward to relative safety.

Stabbed 14 times in his arms, chest, abdomen, back, legs and forehead, it then took multiple teams of surgeons — including two colorectal surgeons, two cardiothoracic surgeons, a spinal surgeon and three plastic surgeons — nearly 12 hours in the operating theatre to save his life.

In the process, Dr Wong’s lung was partially removed to stem profuse bleeding from a deep wound to his back that had contributed to losing his entire blood supply during the operation.

Lack of security

Dr Wong had not recognised his attacker. He later learned that he’d been part of a team of people treating the patient. Mentally ill, the patient had poorly managed schizophrenia, and the attack on Dr Wong was the outcome.

Asked what could be done to reduce the risk of similar such attacks, Dr Wong’s views are clear: hospitals need to reduce publicly accessible areas and beef up security.

“Why do we have so many publicly accessible areas in a hospital? It makes no sense,” he said. “In most hospitals, the general public can walk through the foyer, take a lift and walk to a patient’s bedside without being stopped.”

Dr Wong would like to see patient wards and other appropriate areas closed to the public, with doors only accessible via security swipe cards issued to staff. Family and friends of patients could ring a doorbell to be given access.

He also believes security guards should be stationed in public areas.

“When do you ever see security in the foyer of any hospital?” Dr Wong asks.

While most hospitals station a security guard in an emergency department where patients might be drunk, on drugs or mentally ill, there are rarely guards in other public spaces such as the foyer.

Dr Wong recalls the attack on heart surgeon Dr Patrick Pritzwald-Stegmann, who died in 2017 from a coward’s punch in the foyer of Box Hill Hospital in Victoria. He believes that having a security guard stationed in the foyer could deter similar such attacks, and even if it didn’t prevent the attack, the guard would be on hand to help.

Management accountability required

While acknowledging that the Victorian Government has put more funding into hospital security since his 2014 knife attack, Dr Wong worries that the current management model for hospitals deters real action.

“Who is responsible for the day-to-day running of a hospital? We don’t have a clear view on that. Is it the board? The CEO? The state government? The federal government? There’s multiple layers of management and a funding model where no-one wants to take responsibility. That’s one of the issues in terms of implementing concrete steps,” he said.

“The policymakers and the people in charge of the day-to-day running of the hospital have to wake up and do something about it.”

New appreciation for life

Dr Wong recognises that he is lucky to have survived the attack and return to work. “You appreciate how precious life is. It can end at any second.”

But it was a long road to recovery: his arms and hands were in splints for six weeks, and he required painful physiotherapy and hand therapy to regain full use of his arms and hands. It was three months before he could work again.

During the time off he realised he no longer wanted to feel like he was on a very fast factory conveyer belt. He now works both in private and public practice, but has fewer patients, preferring to spend more time with each one. “It’s better for me, and a better outcome for the patient,” he said. The change has reduced his stress levels and given him more time with family.

The attack has also given him a new perspective on his patients. “I feel more empathy towards them,” he said. “I have a deeper understanding of what they’re experiencing, and how disruptive a serious disease condition can be to their lives.”

False sense of security

But the attack has also made Dr Wong acutely aware of his personal safety.

“As a doctor, even as a nurse working in a large hospital, we often have this false sense of security because there are so many people around,” he said.

“Now I realise that this is not true. All it takes is someone with a small knife and you can be seriously damaged; you can be killed. I accept we cannot total stop violence, but we can reduce it.”

Some patients wait 6 years to see a public hospital specialist. Here's how to fix this

Australian research spanning more than a decade suggests there are ways to reduce waiting lists...

Reusing medical equipment is good for the planet. But is it safe?

A new study tested replacing just one kind of item — single-use absorbent pads, known...

Stewardship and sustainability: environmentally minded medical products

Australia's health sector produces twice as much carbon emissions as aviation. But with...

![[New Zealand] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89856/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)

![[Australia] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89855/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)