COVID-19 in Australia: what have we learned?

COVID-19 has highlighted risks associated with globalisation and the associated threats to health and security. The interconnectivity of individuals moving locally, regionally, nationally and internationally underpins the different types of containment and mitigation measures to prevent and control the spread of the infection.1

In Australia, the first wave of COVID-19 infection was associated with imported cases from overseas. On 25 January 2020, Australia reported its first confirmed case of imported COVID-19 from Wuhan, China, where the pandemic originated.2-4 In the following two months, the majority of cases in Australia came from international travellers returning from China, Iran, the United States, Europe and passengers on board the Ruby Princess cruise ship.5 In response, an Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan was activated by the Australian Government on 24 February, outlining four key strategic objectives aiming to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the community (Figure 1).6

The first objective aims to characterise the nature of the virus and the clinical severity of the disease in the Australian context. It was soon confirmed that the clinical symptoms of COVID-19 included fever, sore throat, cough and difficulty in breathing,7 with a main mode of transmission via direct contact with infected people and indirect contact by contaminated surfaces with infectious droplets. The incubation period has been reported to be between 1–14 days, with increased mortality and morbidity associated with older people and immunocompromised individuals. Asymptomatic carriage of COVID-19 has been confirmed, which may add barriers to case identification, contact tracing and the actual practice of infection prevention and control (IPC) measures in the community.7

The second objective focuses on reducing the transmissibility, morbidity and mortality of the disease. In terms of case importation, the Australian Government has progressively imposed border restrictions since 1 February. What started as a travel ban from mainland China rapidly evolved into restricted entry to all foreigners and a total ban on overseas travel for residents as of 24 March.8 For travellers arriving in Australia by air or sea, case isolation and quarantine started in early February at designated hospitals, later changing to home and hotel quarantine as case numbers increased during March. Household members and close contacts were required to quarantine at home and get tested, should symptoms arise.8 Since 28 March, all overseas travellers have been required to go into government-approved mandatory hotel quarantine for 14 days, to further prevent the risk of imported spread of COVID-19.

To reduce interstate transmission, border closures occurred across all states and territories from late March, with each jurisdiction enforcing their own set of entry requirements.9 To decrease mortality, physical distancing measures were implemented across the nation. Vulnerable groups were encouraged to remain at home, except for emergencies, and to seek support from family and carers for food delivery and other essential services.10

Public health orders across Australian jurisdictions significantly restricted the movement of individuals, with travel imited to essential purposes only. Employers across Australia directed their employees to work from home to limit the spread of COVID-19.11,12 In terms of education, Australia’s states and territories kept schools open during the pandemic. Remote learning was implemented while attendance was recommended to be limited to children of essential workers and those without other care options.13

For all activities involving groups of individuals, keeping a physical distance of 1.5 metres was encouraged. Businesses had to comply with a new one person per 4 m2 policy within their facilities.14 Although restrictions to gathering and movement were staged differently across states and jurisdictions,8 the end of March saw cancellation of various entertainment and sporting events and closure of gyms and clubs. At this time heavy fines were enforced by the police for those not adhering to physical distancing measures.5

The scale of the pandemic brought never-seen-before challenges to the health system, forcing the Australian Government to find ways to support it, which is objective three of the Emergency Response Plan.

Mobile and drive-through testing facilities were introduced in hotspots to reduce the strain and support health systems. Prior to the pandemic, telehealth had been growing at a slow pace, but its acceleration became a priority to help reduce the risk of community transmission and provide protection for patients and healthcare providers.15

We have seen the rapid implementation of the following actions: expansion of intensive care unit (ICU) capacity to curb the surge in number of COVID-19 cases; increased PPE supplies across the country; cancellation of elective surgery and other services to reduce risk of COVID-19 transmission to both staff and patients; and a greater partnership between public and private health systems.5

Objective Four focuses on the community and COVID-19. Two apps have been developed by the Australian Government for the general public including the Coronavirus App, which provides the latest pandemic updates and advice from official sources, and the COVIDsafe App, which uses Bluetooth to trace cases and close contacts.15 Additionally, official public announcements have been provided daily across social media platforms and news outlets.16

Free, accessible and increased COVID-19 testing across jurisdictions maximises opportunities for the public to take responsibility for their own health and safety.10 Australia’s success in mitigating the first wave can be attributed to enforced social distancing, effective border closures, high testing rates, as well as meeting the nation’s four objectives in the response plan (Figure 2).5

© 2020 Commonwealth of Australia as represented by the Department of Health

The robust identification of new cases and effective contact tracing allowed restrictions to ease in June 2020, with businesses such as gyms and bars reopening under implemented COVID-19 safety plans. However, in Victoria, inadequate non-compliance with public health orders (eg, breach of mandatory hotel quarantine protocols) led to extensive community-acquired COVID-19 cases in August.

These events contrast with the first wave, where only 10% of the 6695 cases were community-acquired.17 The Victorian Government has implemented strict close-contact tracing protocols in open venues to enable active surveillance around the rising number of confirmed cases. On 2 August, Victoria commenced a stage 4 lockdown by enforcing an 8 pm to 5 am curfew and limiting the reasons to leave home to food, exercise, work and care. Additionally, strict border closures have been put in place across Australia.18

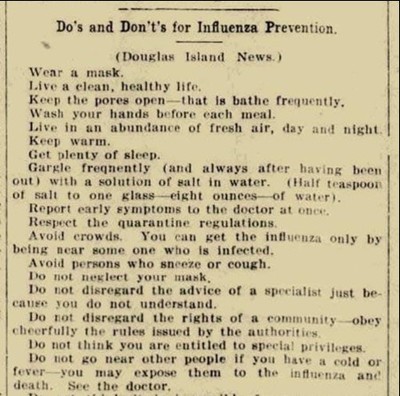

History shows us that although devastating, what the world is experiencing now is not unusual. The 1918 Spanish Flu IPC recommendations to the community are almost identical to the current public health recommendations (Figure 3).

COVID-19 will not be the last emerging infectious diseases affecting global population. In the absence of effective treatment and vaccines, the implementation of a comprehensive package of containment and mitigation strategies has enabled the control of COVID-19 spread. Sustained adherence to IPC protocols, provision of accessible and affordable testing, and enforcement of strict physical distancing and contact tracing measures have all have helped to contain the spread of COVID-19. The success of these measures is largely dependent on public compliance and community engagement. Learning from these collective experiences will help public health units improve infection prevention and disease control responses and plans in future pandemics.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7184197/.

- https://www.theguardian.com/science/2020/jan/25/coronavirus-five-people-in-nsw-being-tested-for-deadly-disease.

- Shaban RZ LC, O’Sullivan M, et al. COVID-19 in Australia: Our national response to the first cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the early biocontainment phase (accepted 28 August at Internal Medicine Journal).

- Shaban RZ NS, Sotomayor-Castillo C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19: The lived experience and perceptions of patients in isolation and care in an Australian healthcare setting (accepted 29 August at American Journal of Infection Control).

- https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMc2011592.

- https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian-health-sector-emergency-response-plan-for-novel-coronavirus-covid-19.

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2760782.

- https://www.pm.gov.au/media/update-coronavirus-measures-24-March-2020.

- Australian Government. Department of Health. Coronavirus (COVID-19) domestic travel restrictions and remote area access [press release]. 27 July 2020.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876201820301945?via%3Dihub.

- https://www.nsw.gov.au/covid-19/safe-workplaces/employers/working-from-home.

- https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/working-home-covid-19.

- https://www.health.gov.au/news/australian-health-protection-principal-committee-ahppc-coronavirus-covid-19-statement-on-17-march-2020-0.

- https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/how-to-protect-yourself-and-others-from-coronavirus-covid-19/limits-on-public-gatherings-for-coronavirus-covid-19.

- https://www.phrp.com.au/issues/june-2020-volume-30-issue-2/stemming-the-flow-how-much-can-the-australian-smartphone-app-help-to-control-covid-19/.

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-27/federal-government-coronavirus-pandemic-emergency-plan/12005734.

- https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-at-a-glance-25-april-2020.

- https://theconversation.com/melbournes-hotel-quarantine-bungle-is-disappointing-but-not-surprising-it-was-overseen-by-a-flawed-security-industry-142044.

Medicine shortages are testing Australia's health system and clinicians need national support

Medicine shortages are no longer isolated supply disruptions. They are escalating and directly...

Mindfulness and endoscopies — a more effective combination?

A UK study involving 231 patients has advocated 'mindful endoscopy' — allowing...

How do different types of pain influence empathy?

Different types of pain influence how unpleasantly we perceive it but also how we empathise with...

![[New Zealand] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89856/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)

![[Australia] Transform from Security Awareness to a Security Culture: A Vital Shift for SMB Healthcare — Webinar](https://d1v1e13ebw3o15.cloudfront.net/data/89855/wfmedia_thumb/..jpg)